Takeoffs and Landings

Along with taxi operations, takeoffs and landings are a primary differentiator between seaplane operations and traditional land-based activities. If one can pilot a land-based aircraft, learning the nuances of seaplane operations is not difficult.

The constantly changing environment in which the seaplane operates will present the pilot with different variables each time. These variables include, but are not limited to, winds, water conditions, boat traffic, etc. The changing variables makes seaplane flying so mean that seaplane pilots never get bored.

Pre-Takeoff Considerations

Like landplane flying, there many pre-takeoff considerations. At a minimum, the pilot should:

- Complete all pre-takeoff checklists.

- Determine wind direction to plan a takeoff route.

- Make sure there is sufficient distance, taking weight and density altitude into account.

- Make sure the takeoff route will be clear of debris, buoys, boats, swimmers, other

aircraft, and any other obstacles. - Pick an abort point: if the aircraft has not become airborne by this point, abort the

takeoff. The abort point is often selected during the previous landing.

Pre-Landing Considerations

In addition to pre-takeoff considerations, there are many pre-landing considerations. At a minimum, the pilot should:

- Make sure there is enough room to takeoff after landing. Seaplanes can land in a shorter distance than what might be needed for takeoff.

- Ensure that the landing area is feasible and safe to land by conducting a reconnaissance. Details on conducting a reconnaissance are discussed under the landing section.

- Study the shoreline if beaching is planned.

- Plan how to approach the dock, ramp, or other designated areas.

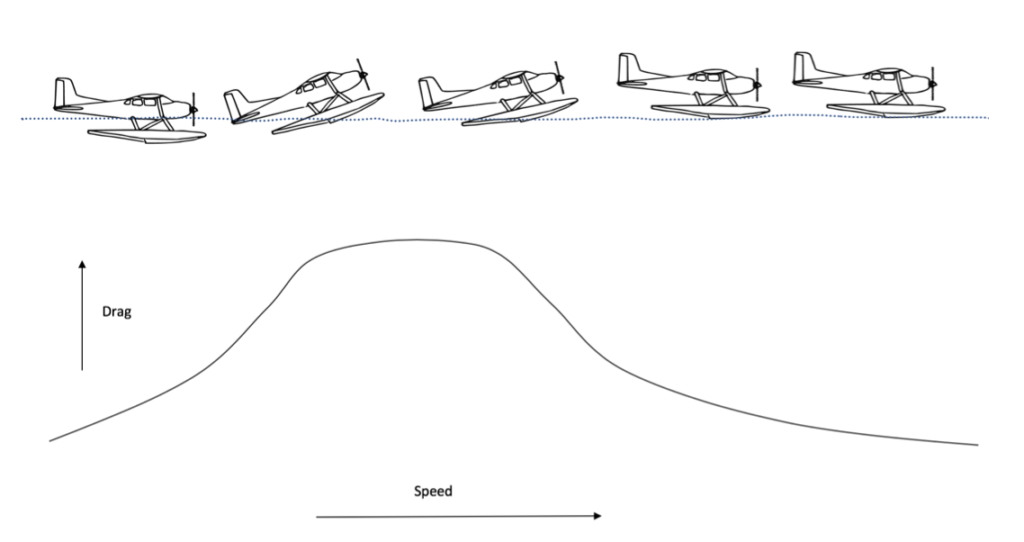

Takeoff Run: The Hump

All of the different water takeoffs will include a takeoff run. This is the same as the takeoff roll for a landplane. However, there are a few differences. The primary difference is the aircraft transitions from the displacement position (deep in the water) to the planing position (or on the step). During this transition, the aircraft’s nose will rise significantly with the application of power. There is a high amount of drag at the start, which will dissipate as the aircraft increases speed and less float area remains in the water. As indicated in the diagram below, the drag curve displays a rise or hump.

River Currents

When conducting river operations, the current is another consideration in addition to the wind. The intent is to minimize the impact of the water on the floats. Normally a plane should take off into the wind to minimize the ground speed at takeoff. If the wind and current are in opposite directions, there are no changes needed to any takeoff or landing techniques. However, if the wind and current are in the same direction, consider a downwind takeoff or landing. A downwind takeoff or landing should only be considered if the winds are light. In light winds a downwind takeoff can take advantage of the current. Taking off with the current is the same as lowering the ground speed, as the ground is moving with the airplane. However, a higher airspeed will be needed, so the benefit is negated with other than light winds. Below are some common wind/current combinations.

No wind: All takeoffs and landing should be with the current.

Opposite directions: The takeoffs and landings should be into the wind and with the current.

Same Direction: In this case, it is up to the pilot. However, if the winds are light, the takeoffs and landing should be with the current. If winds are strong, the takeoffs and landings should be into the wind. Generally, if the wind is greater than the current, takeoffs and landings should be into the wind.

DEFINITIONS:

Hump Speed: The speed during the takeoff of a seaplane at which the resistance of the float or hull reaches its maximum.

Hydrodynamic Forces: Forces relating to the motion of fluids and the effects or fluids acting on solid bodies in motion and relative to them.

Hydrodynamic Lift: For seaplanes, the upward force generated by the motion of the hull or floats through the water. When the seaplane is at rest on the surface, there is no hydrodynamic lift, but as the seaplane moves faster, hydrodynamic lift begins to support more and more of the seaplane’s weight.

Porpoising: A rhythmic pitching motion caused by an incorrect planing attitude during takeoff

Skipping: Successive sharp bounces along the water surface caused by excessive speed or an improper planing attitude when the seaplane is on the step.

QUESTIONS:

What are the keys to a glassy water landing? Establish a last known visual reference and then conduct a stabilized descent of approximately 50-100 feet per minute, but no more than 150 feet per minute. Remember: pitch, power, patience. No turns should be made after the last known visual reference.

When conducting river operations, should a pilot land with the current or into the wind? This will depend on the strength of the wind and current. If the winds are light or calm, it can be better to take off and land with the current. When landing with a strong current, the maneuverability can be reduced if a turn is made against the current. Ideally the pilot will be able to take off with the current and into the wind. Operations going downwind against the current should be avoided. This situation produces excessive water drag and will cause a strong nose down pitching moment on landing.

Would a pilot prefer a left or right crosswind? The pilot would prefer a right crosswind as the left turning tendency of the aircraft counteracts the right crosswind some. Conversely, a left crosswind compounds the left turning tendencies of the seaplane.

What size wave is too big to for water operations? The waves may be too great for operations when the wave height exceeds ½ the size of the float, or if there are less than two wave crests touching the float at one time.

Go To Subsection – Normal Takeoffs and Landing

Next Section – Securing the Seaplane