Securing the Seaplane

A seaplane pilot should become familiar with all facets of water movement. This is one area where experience really pays off. Becoming better at moving the seaplane on the water will provide a better experience for passengers and decrease the likelihood of damage to the aircraft. Additional water-based tasks performed by the seaplane pilot include docking, mooring, and ramping.

Navigating to the dock, ramp, or other

Many times, a seaplane will be secured in a facility with a dock, ramp, or mooring buoy within a marina or harbor. The nature of these facilities means that the pilot will likely need to navigate the seaplane near obstacles such as other docks, pilings, jetties, seawalls, etc. A combination of taxiing and sailing can be used to approach safely. Below are some items to consider.

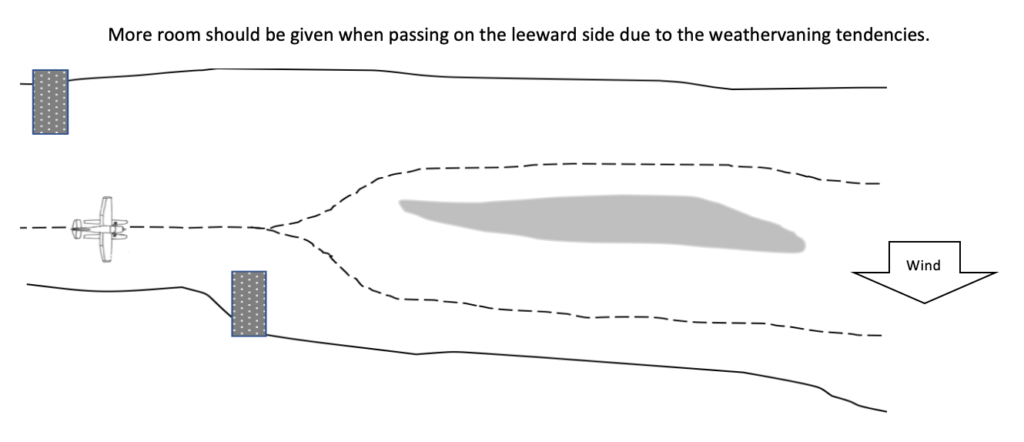

- Due to the weathervaning characteristics, the seaplane easily turns into the wind. This principle can be used when planning a route to the dock. In general, it is safer to approach from the windward side; if clearance of an obstacle is in question the pilot can easily turn way (or into the wind). More room should be given when passing an obstacle on the leeward side. If the seaplane weathervanes, it may turn into the obstacles. As noted previously, the taxi route should be planned to take advantage of the wind and weathervaning characteristics of the seaplane.

- When approaching the dock or ramp, the pilot should remember “headsets, harness, and hatches” as a reminder to remove his or her headset, unbuckle seatbelts, and open the door. Once at the dock or ramp, the pilot may need to get out quickly.

- As most seaplanes cannot reverse the pitch on the propeller, there will be constant thrust if the engine is running. This thrust will move the seaplane on the water. To slow the engine down even more, the engine can be operated with carburetor heat on (if equipped) and/or running on only one magneto. If running on one magneto, the fuel/air mixture may need to be leaned. However, the pilot must ENSURE TO TURN ON BOTH MAGNETOS AND MIXTURE FULL RICH PRIOR TO THE TAKEOFF RUN.

- The amount of time an amphibious plane is left in the water should be minimized. When the seaplane is on the water, the landing gear is submerged.

Docking

Docking a seaplane is similar to docking a boat, with one exception. For most seaplanes, the engine needs to be shut off while approaching the dock in order to slow down. There are a few other considerations when docking.

- The magnetos should be turned off whenever the propeller is stopped. A helpful deckhand may grab and turn the propeller, such as to check themselves if they fall.

- If a strong wind is blowing towards the dock it will be easiest to sail rearward to the dock.

- If there is a helper, they should be briefed not to go in front of the strut; this practice should prevent propeller strikes.

- The location on the dock where others may walk should be considered. That is, the seaplane may be moved to a location on the where it is easier for others to walk on the dock without hitting the wings.

- When docking with an amphibious plane, avoid nosing in with the front gear. The front gear is fragile and more easily damaged.

- If an amphibious plane must be nosed in, do so slowly to avoid an impact on the front gear.

- To avoid hitting the dock with the tail, avoid sharp turns when departing the dock.

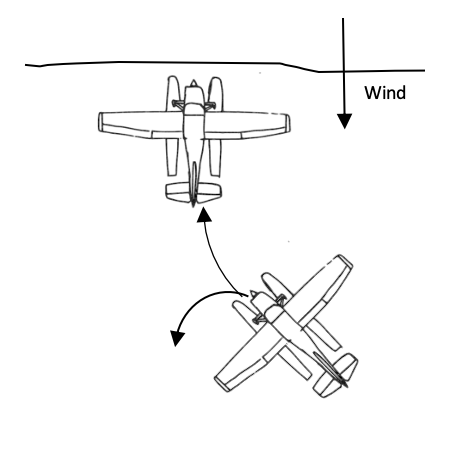

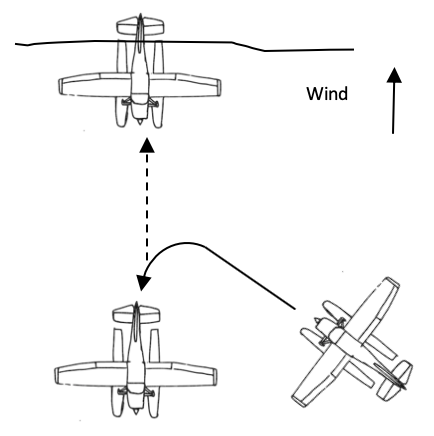

Below are some examples of docking. The options are varied, but a combination of taxiing and sailing will allow safe access to most docks.

The seaplane’s weathervaning tendency should be used to the pilot’s advantage. Plan ahead. In this case, approach so that the turn into the wind does not push the aircraft away from the dock.

Using the same dock, but with an obstacle, such as an anchored boat, the pilot may be better off sailing back into position. Such a situation is why it is a good idea to learn how to sail.

Ramping

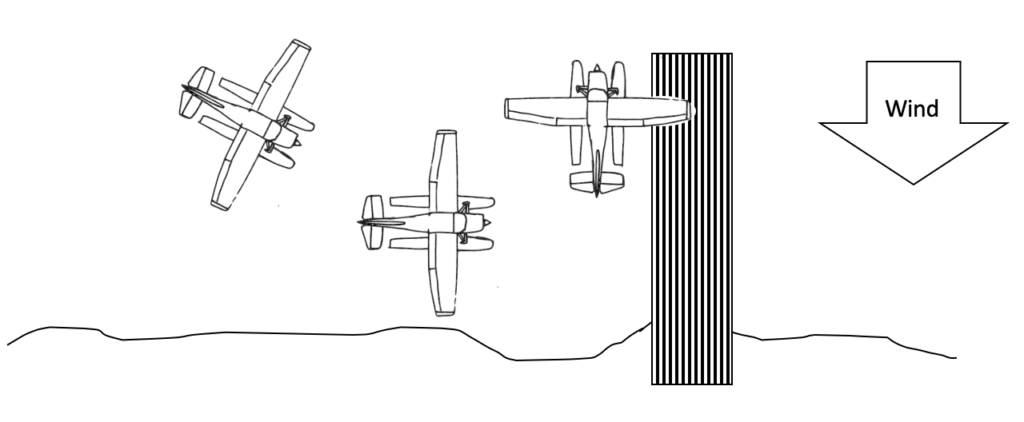

The landing and taxi should be planned to set the pilot up for success. If the wind is parallel to the ramp, the ramp should be approached downwind so that the turn to the ramp takes advantage of the weathervaning tendencies of the seaplane. The pilot should:

- Add power when approaching the ramp. There should be enough speed to create a bow wave that cushions the floats when they contact the ramp.

- Use caution when stepping onto the ramp; ramps tend to be slippery.

- Not use concrete ramps when flying an aircraft on straight floats.

- Ensure to extend the landing gear on an amphibian if it is to be taxied onto a ramp. The landing gear can take some time to extend. The brakes may initially be ineffective when exiting the water, so caution is warranted.

- Line up with the ramp. Do not make any turns when ascending the ramp. To keep the nose down, use full flaps and full forward on the elevator. Do not stop while ascending.

- Taxi amphibians very slowly down ramps.

- Ensure to observe any changes in ramp angle as an amphibian could possibly high center when entering or exiting a ramp.

- Keep a close watch for spectators. It is likely that amphibian operating on a ramp will attract onlookers. These spectators may not understand the dangers of the propeller and the limited visibility of the pilot. Keep a close watch for people and preferably have safety personnel outside guiding the plane.

Like other operations, the weathervaning tendencies should be used to the pilot’s advantage. In the example above, the plane should be taxied straight to the ramp, or the last turn to the ramp should be into the wind.

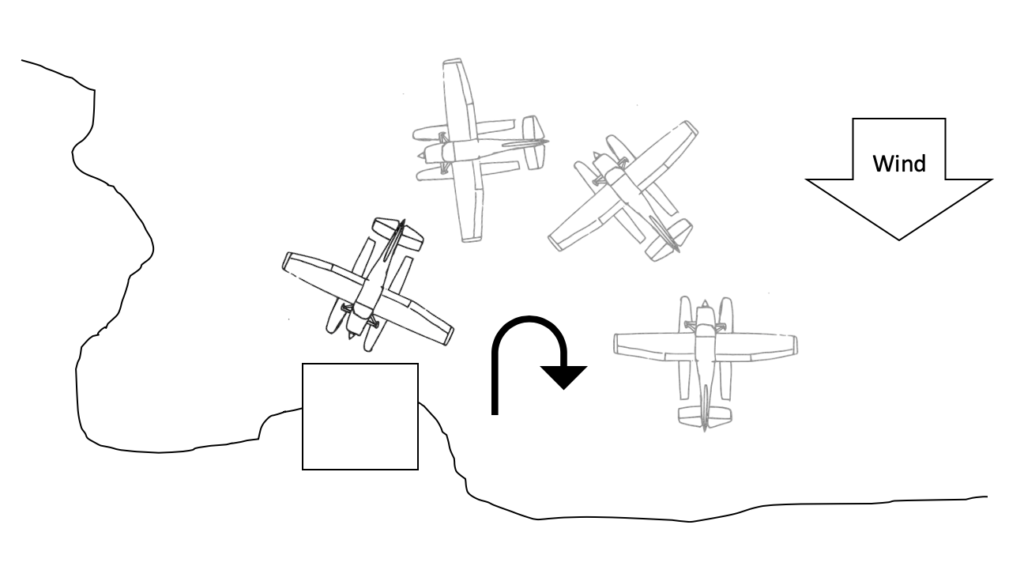

When departing a dock/ramp, consider the wind as the seaplane will want to weathervane into the wind and there may be enough rudder authority to counteract the weathervaning. That is, the aircraft should be pushed off dock/ramp in a direction so that when the seaplane weathervanes, it will not to be a problem. Avoid pushing off where the weathervane characteristics would be bad. In the example below, the seaplane should be pushed off to the right, instead of the left, where the aircraft might hit the shore.

Another option would be to physically turn the aircraft around on the ramp before departing. This way, it could be just taxied off the ramp and taxied straight into the wind.

Beaching

Beaching is the act of bringing the seaplane to the shoreline. A primary concern is to ensure that the beach it appropriate for such activity. The beach should have a gentle soft slope. Any beaches that are rocky or contain significant amounts of vegetation should be avoided. The wind will determine how to approach the beach. The three primary conditions are detailed below.

Nose In: Directly Into the wind

If the wind is coming from the shore, the aircraft can be idle taxied all the way to the beach. When nearing the beach, the water rudders should be lifted. Once on the beach, the seaplane can be manually turned around for departure.

The approach should be at a slight angle and then straightened out. Arriving at an angle allows the pilot to inspect the beach and ensure that it is acceptable and won’t damage the floats. If the pilot sees something they don’t like, they can turn away much easier than if at 90 degrees to the shore. This is especially needed with amphibious aircraft as the gear mechanism could be more easily damaged than straight floats.

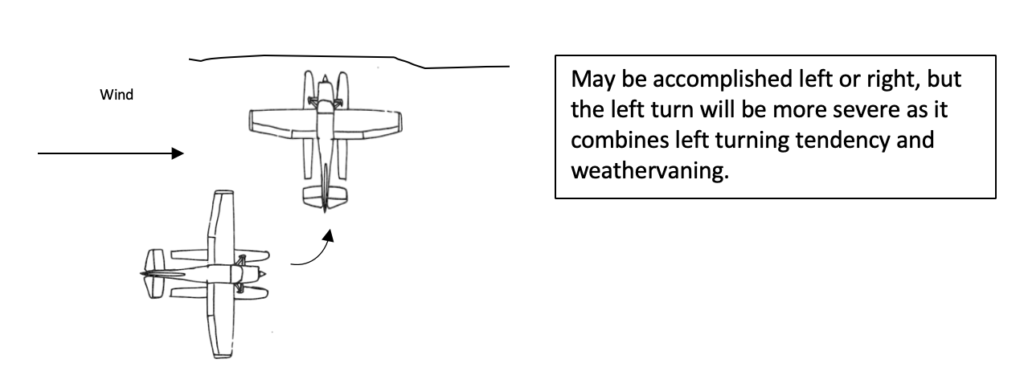

Crosswind: Wind blowing along the shore

If the wind is blowing along shore, it is best to parallel the shore downwind and then turn towards the shore so that float contact is made to bring aircraft perpendicular to the shore. This should not be attempted in strong crosswinds as is may be difficult to control. With practice, the pilot should find the right timing and power settings to handle stronger and stronger crosswinds.

Sail In: Wind blowing towards the beach.

If the wind is blowing towards the beach, it is better to get close to the beach, then turn and sails backwards the final 100 feet or so. Ensure the water rudders are up. This should be done when sailing anyway, but it is really important when beaching, to avoid damaging the water rudders.

The longer the sailing portion, the more difficult it will be to beach on the designated spot. Sailing the shortest distance possible is better.

Departing the Beach

Prior to leaving, the seaplane should be pushed far enough out so that neither float is significantly resting on the bottom. An unanticipated turn may be initiated if one float is resting on the bottom and the other not. If there are obstacles nearby, this could cause a problem.

Mooring

Mooring is the process of securing the seaplane to a buoy. This task is similar to docking but approaching a buoy instead of a dock. Approach a buoy on the outside of the floats. Do not ever straddle a buoy. Whenever possible, make the final positioning into the wind.

Anchoring

To secure the aircraft on the water or on the beach, it should be anchored. The choice of anchor type depends to the pilot, but the Lewmar Claw or Bruce anchor works well for seaplanes. They are light weight and provide good holding power. Below are some considerations for anchoring.

- Anchoring is only suitable for light winds and short periods of time.

- The line should be about seven times the depth of the water.

- Attach the anchor to the mooring cleats on the float bows.

- With the engine off, throw the anchor into the water and allow the plane to drift backwards.

- Watch reference points on the shore. The plane is anchored once the drifting is stopped.

DEFINITIONS:

Anchor: A heavy hook connected to the seaplane by a line or cable, intended to dig into the bottom and keep the seaplane from drifting.

Beaching: Pulling a seaplane up onto a suitable shore so that its weight is supported by relatively dry ground rather than water.

Dock: To secure a seaplane to a permanent structure fixed to the shore. As a noun, the platform or structure to which the seaplane is secured.

Moor: To secure or tie the seaplane to a dock, buoy, or other stationary object on the surface.

Ramping: Using a ramp that extends under the water surface as a means of getting the seaplane out of the water and onto the shore. The seaplane is typically driven under power onto the ramp and slides partway up the ramp due to inertia and engine thrust.

QUESTIONS:

When mooring to a buoy, what is a major concern when approaching the buoy with the seaplane? The seaplane should be brought up to the buoy on one side or the other. Do not straddle the buoy with the floats as this may damage the floats. When approaching the buoy, the final approach should be into the wind to facilitate taxiing.

How should a beach be approached if the wind is blowing towards the shore? The beach should be approached at a 45-degree angle and with a turn into the wind and then a sail backwards to the beach. The sailing portion would be about 100 feet.

What is a concern with an amphibian when beaching? The landing gear is more fragile than straight floats so do not hit anything on the beach.

What is a concern with an amphibian for securing in the water? Do not leave the amphibian in the water for long periods of time. Water is hard on submerged landing gear. The benefit of the amphibian is that it can be taken onto land. Take advantage of that capability.