Normal Takeoff/Landing

The normal takeoff and landing, as one might expect, are the basis for all other takeoffs and landings. Key characteristics of the takeoffs and landings are outlined below.

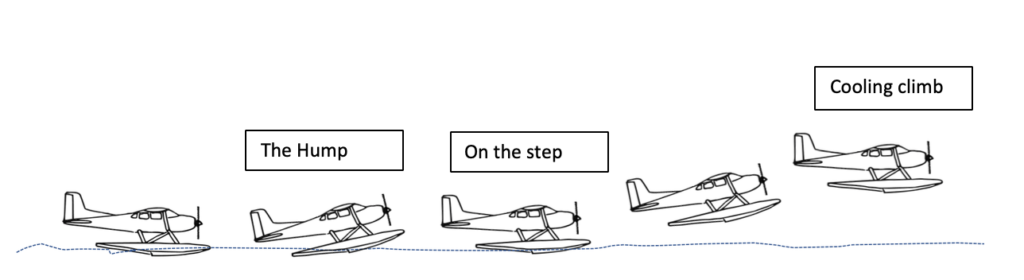

Normal Takeoff:

- Most takeoffs can be made directly into the wind.

- Water rudders should be retracted to prevent them being damaged.

- Right rudder is used to counteract the left turning tendency during takeoff.

- The yoke or stick should be held full aft while power is added.

- The yoke or stick is moved forward to get on the step.

- The aircraft should be flown off the water. Do not try to force it off early.

- A cooling climb should be conducted after clearing any obstacles. Seaplanes usually have larger, more powerful engines, which benefit from climbing at a faster airspeed or with reduced power for better cooling.

During the takeoff run, should the aircraft begin porpoising, the corrective actions are the same as when conducting a step taxi. These actions are discussed under the taxi section.

During the takeoff run, should the aircraft begin porpoising, the corrective actions are the same as when conducting a step taxi. These actions are discussed under the taxi section.

Reconnaissance before landing:

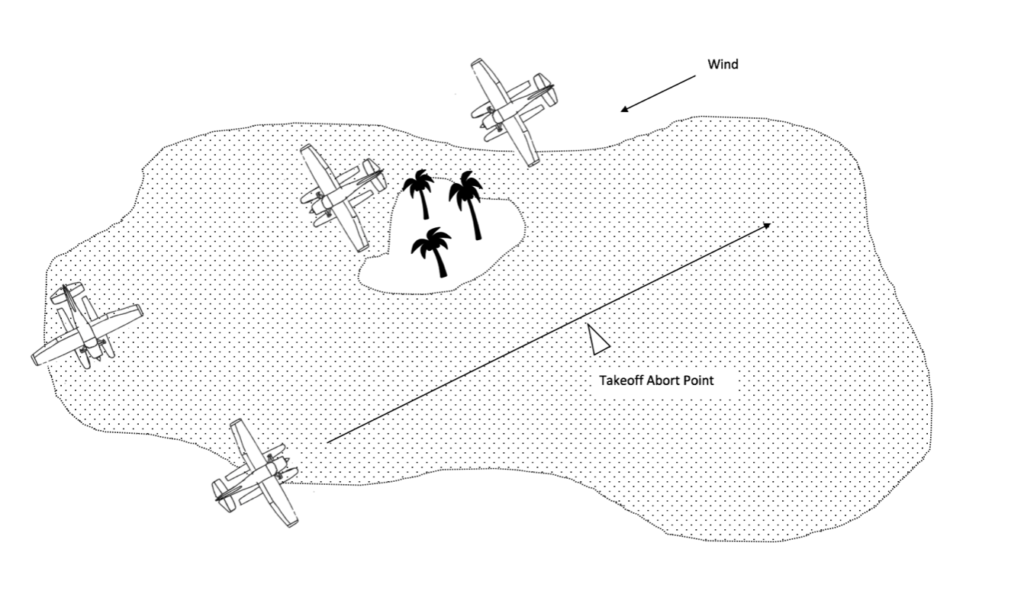

One major difference with seaplane flying compared to most general aviation flying is operating in a non-airport environment. The pilot will likely have to determine the suitability of the landing area without the benefit of the normal airport information. A reconnaissance is performed to determine the suitability.

The reconnaissance is generally conducted in two phases, a high reconnaissance and a low reconnaissance. The high reconnaissance is conducted from approximately 500 feet AGL. At this altitude, the pilot performs a preliminary review of the suitability of the landing site. The following mnemonic is useful in remembering to review several key items. The Five Ws.

Wind/Water: What is the direction and intensity? Wind indicators outlined in the weather/environmental section should be used.

Wires: Are there any obstacles such as high-line wires? Wires can be difficult to see, so the pilot must pay attention. If there are poles, there are likely wires.

Way In: Is there an obstacle free approach into the area? This review would include identifying a way into the dock, beach, or other designated area.

Way Out: Is there an exit strategy if the approach needs to be aborted? This phase includes identifying how the departure will be conducted after the takeoff. At the same time, an abort point should be identified for the next takeoff.

What If: Are there any other issues, such as boats, jets skis, etc.? As this is a non-airport environment, be prepared for the unexpected.

Once the high reconnaissance is conducted, a low reconnaissance is conducted while on final approach. While on final approach, the pilot continues to monitor the landing site for items that might not have been visible during the high reconnaissance. The pilot is also looking for items that might have changed, such as boats, or other vessels. As this is an off-airport landing, be vigilant for the unexpected.

During the high-reconnaissance, do not lose sight of the landing spot. Keeping the spot in sight, such as out the pilot-side window, minimizes the likelihood of mistaking a similar location as the one the high reconnaissance was just conducted. In addition, to the 5Ws, there are a few other points to remember.

- During the reconnaissance, keep the aircraft in a position to land if there is an emergency, such as an engine failure.

- The reconnaissance can be done to the left or right. If obstructions are not a problem, left turns should be used as the area would be in the pilot’s view (assuming left seat in tandem aircraft).

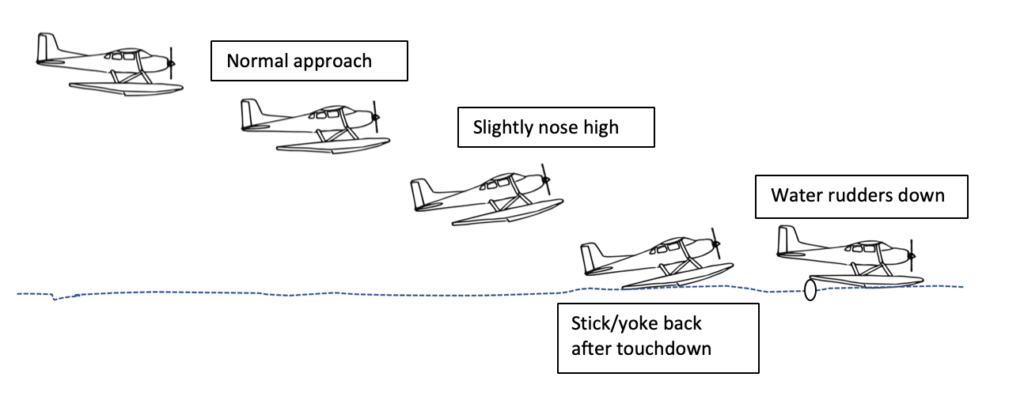

Normal Landing:

- In an amphibian, the landing gear must be retracted for water landing. Landing on the water with the wheels down is disastrous. If a mistake is to be made, it is better to land on a runway with the wheels up, than land on the water with the wheels down.

- Land into the wind.

- Pick a touchdown area, even if there is plenty of room.

- Make a stabilized approach.

- Touch down slowly in a slightly nose high attitude.

- Apply full aft yoke and idle power to slow the aircraft.

- Lower the water rudders to provide steering after settling into the displacement taxi.

Skipping During Landing

Due to excessive speed and an improper pitch attitude at touch down with the water, the plane may bounce upon contact with the water. This bounce is known as “skipping”. Unlike a porpoise, the skip is a hard bounce from wave to wave. Basically, the floats are skipping on the water much like skipping a stone across a pond.

A primary factor with skipping is excess speed on landing and an improper attitude. With glassy water, excess speed and a low pitch attitude may cause the floats to skip on the water. During non-glassy water conditions, skipping can occur with too much speed and a higher than normal pitch attitude. The seaplane will bounce from wave to wave. Although it can be confused as a porpoise, skipping is a hard bounce while the porpoise is more of a rocking motion.

To correct for skipping, back pressure on the elevator control is increased and sufficient power is added to prevent the floats from contacting the water. The proper pitch attitude is established, and power is reduced gradually to allow the seaplane to settle gently onto the water. Skipping oscillations do not tend to increase in amplitude, as in porpoising, but they do subject the floats and airframe to unnecessary pounding and can lead to porpoising.

Although skipping primarily occurs during landing, it can occur anytime the seaplane is on the step. However, current float designs are not as susceptible to skipping as older designs. Skipping is unlikely to occur, and is hard to demonstrate, but the pilot should understand the concept and how to address it should it occur.